Lili Bita – Women of Fire and Blood: Ancient Myths, Modern Voices, Reviewed by Rochelle Lynn Holt

(www.angelfire.com/blues2/rlynnholt)

In Women of Fire and Blood (Somerset Hall Press, 2007), author Lili Bita includes a section she calls “Instead of a Preface: A Confession,” in which she writes: “Apollo says, women are the mere receptacles of masculine seed, the passive carriers of life… Pericles says, silence brings dignity to women.” Bita rejects this negative hearsay to commune directly with Media, Clytemnestra, and Helen of Troy.

A talented poet, novelist, and short fiction writer, Bita has devoted her life to portraying Greek women on stage in myriad cities, states, and countries. An immigrant who has told her story in her memoir Sister of Darkness (also from Somerset Hall Press), she feels she’s “been the medium of [women’s] dictation” – but not to free these ancient women, for “they have freed” her.

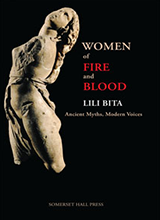

Readers have known much of male Greek gods, the men who invented the word myth to embrace their souls beyond mortality. However, Bita’s poems are beyond myth as Greek women come alive, becoming flesh and blood beyond statues like the one on the cover of a maenad sculpted by Skopas. These women now have a chance to sing, dance, scream, and flaunt their lusty reality to change the face of academic interpretations, too often slanted.

In the first stanza of “And the Ashes Were Helen’s,” Eleni, “sixteen and a virgin” knows her fate since “Agamemnon hides a sacrilegious passion” for her. But, Agamemnon is “my sister’s husband,/my husband’s brother, Agamemnon, the killer.” In stanza two, she is raped. From “III:”

Marriage is a manual of orders.

Mine was no different….

Then I saw him in the war games,

Greece against Troy…

I laid the laurel wreath

on his conquering brow.

I touched the fingers…

I am burning, I thought,

I am burning. I need air.

But this was a Trojan prince,

and I, the Queen of Sparta.

In the fourth stanza, Eleni (Helen) says she was not seduced by Paris. She went with him gladly, because Agamemnon wanted her back. Iphigenia was not merely the daughter of Agamemnon “sacrificed by her father to raise favorable winds for the expedition to Troy,” she was woman in child, aware of her fate. In the poem of her name, stanza II, she says: “I saw the child in my dream/adorned like a bride/in a black shroud/instead of a wedding ring/the blade of a knife.” And, when “the knife’s blade” severs her neck from body, she knows she is “not your little girl,/ father, for whom you/propped your legs/on the ornamented desk/so that I could ride, ride your knees/and fall into your arms?”

Finally, Bita imagines Medea saying:

…In my country

I lit the waves

with torches

culled poison

from the stars

for a cureall…

Hear a mother’s heart

and judge for yourself.

These are not mere portraits of ancient women whose personalities have been as transparent and elusive as their face and figures. The essence of their humanity comes alive like paintings whose subjects are allowed to speak beyond a whisper.

These are brilliant poems that read like short stories, translated flawlessly by the poet, critic, and historian Robert Zaller. Readers not well-acquainted with these heroines should consult the “Dramatis Personae” at the end of the book before reading the narrative poems.