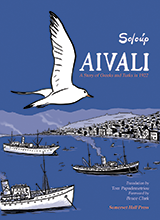

New Graphic Novel About Greeks and Turks in 1922

Reviewed in the Pappas Post online. Review by Gregory Pappas, The Pappas Post, December 16, 2019.

Before I even turn the first page of this new graphic novel, a song comes to mind just by reading the title and some of the press about it.

Glykeria sang it appropriately in a concert she performed — even more fittingly — in Smyrna last September. “I’m a Turk, you’re a Greek,” the lyrics go, “You believe in Christ and I in Allah… όμως κι οι δυό μας άχ και βάχ.”

“But our angst is the same.”

It’s a well-known song about the shared fates, pains and joys of a Greek and a Turk, Yianni and Mehmet.

We don’t know what ever came of Yianni and Mehmet of this particular song as the lyrics don’t reveal the full story. But what we do know is that there were millions of similar stories of Greeks and Turks whose lives were changed forever in the 1920s after war, genocide and a forced exchange of populations.

Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922 is a new graphic novel in English translation that dramatically tells the story of the era from the perspective of those lived and died at this time — and their third and fourth-generation descendants.

The author is a well-known political cartoonist Antonis Nikolopoulos, whose pen name is Soloup (part of his last name spelled backward). He is a descendant of refugees from Asia Minor. All four of his grandparents were Greeks who were born on the Turkish coast, with two of his grandmothers coming from Smyrna.

The graphic novel retells the stories of four people with ties to the town of Aivali (Aivalik in Turkish). Three are Greeks who wrote memoirs about their lives before and after the Catastrophe: Fotis Kontoglou, who became famous as a Byzantine iconographer; Elias Venezis, a well-known and respected Greek author; and his sister, Agapi Venezi-Molyviati. The fourth is Ahmet Yorulmaz, a second-generation descendant of Greek-speaking Muslims from Crete who were removed to Aivalik.

The fifth story is that of the author himself, which frames the other stories. He tells of going on a summer outing to Aivali, and seeing all the houses once inhabited by Greeks. During his outing, he met a Turkish family with their own story of displacement.

These events forced him to reflect on his family history and ultimately led him to write Aivali. As a cartoonist, he knew that the most effective format for him to write his story would be as a graphic novel, a format that can reach many new audiences, especially the young.

Although the events in the book took place almost 100 years ago, they continue to have a huge impact on present-day Greece. Furthermore, the refugee crisis of that time has resonance today, as Greece struggles to deal with another refugee crisis.

The Historical Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, Greeks and Turks lived alongside each other in the town of Aivali and other places along the Aegean Sea and throughout Asia Minor as they had for centuries during the Ottoman Empire, sometimes peacefully and sometimes under extreme duress.

Twenty years later, they were caught in the middle of the Greek-Turkish War, which ended in Greece’s defeat in 1922. The Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 governed a population exchange, which resulted in the expulsion of Greek Orthodox Christians from Turkey to Greece and a smaller number of Muslims from Greece to Turkey, even if though they had never lived in the other country. These events are known to Greeks as the “Catastrophe” or the “Asia Minor Disaster.”

More than 1 million Greek Orthodox from Turkey became refugees in Greece. At the time, Greece had a population of around 5 million, which meant that the absorption of all these refugees caused huge economic, cultural and political strains in Greece.

According to some sources, two out of five Greeks today have at least one grandparent from Asia Minor, just like the author of Aivali.

The book was originally published in Greece and was translated into Turkish, French, and Spanish (forthcoming). It has been acclaimed internationally — and justifiably so — as it brings together a dream team of content creators, each contributing their specialty and expertise.

Bruce Clark, an editor for The Economist and the author of Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey, wrote the foreword.

In Greece, Kathimerini wrote: “Following in the footsteps of Art Spiegelman, Marjane Satrapi, Joe Sacco, or Jacques Tardi, Soloup, against the background of blood-stained chapters of history, focuses on human tragedy.”

In France, Science & Vie Guerres & Histoire wrote that Aivali is “a beautiful reflection on the creation of identities and the relevance of borders.” And in Turkey, Radikal Kitap wrote that it is “a contemporary mirror of historical tragedies that, on this land we live on, tend to somehow repeat themselves, like a broken record.”

The author is a well-known political cartoonist and caricaturist who collaborates with major newspapers and magazines in Greece. He studied political sciences at the Panteion University and obtained a Ph.D. (Cultural Technology and Communication) at the University of the Aegean. He has published 13 books with comics and cartoons and his Ph.D. dissertation on the history of comics in Greece.

His first graphic novel, Aivali, received the prize of the best comic and of the best scenario in 2015 Comicdom Athens. It is the first graphic novel to be the subject of an exhibition at the Benaki Museum, from where it has travelled throughout Greece.

The English translator, Dr. Tom Papademetriou, is the Constantine and Georgiean Georgiou Endowed Professor of Greek History at Stockton University. A graduate of Hellenic College/Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, Dr. Papademetriou received his Ph.D. from Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies in Ottoman History.

His research focuses on the history of non-Muslims under Ottoman rule. He directs research seminars at the Center for Asia Minor Studies in Athens, Greece and has co-authored a play, “Stones From God,” based on oral histories of Cappadocian Christians in the late Ottoman period.

The finished product is a perfectly performed zeibek dance, masterfully improvised, on the quay of a fishing village that could be on either side of the Aegean.